Political uncertainties and market speculation

Oct 29, 2019 09:36 AM ET

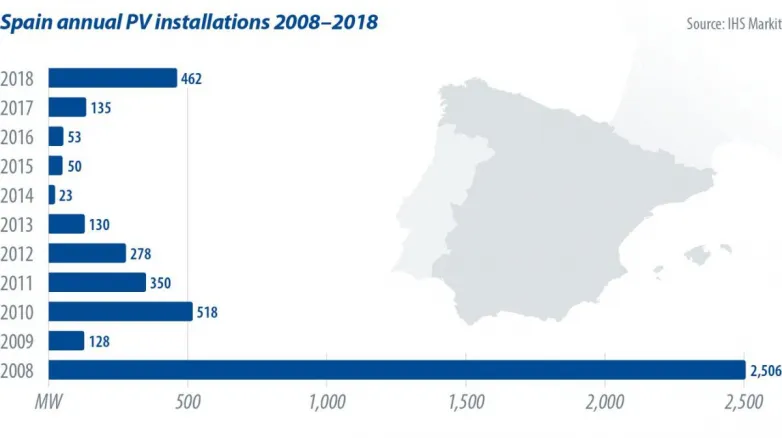

- After several years of stagnation, Spain has started to see a revival in its PV market, writes IHS Markit’s Maria Chea. The country’s newfound growth has been due to a combination of tender and private PPA projects, along with decreasing component costs.

In order to meet its 2020 targets, the Spanish government returned to incentivizing renewables in 2016, with two auctions launched the following year. The 2017 auctions awarded 3.9 GW of PV. IHS Markit forecasts Spain will install approximately 20 GW from 2019 to 2023, with initial demand coming from projects awarded in the third renewable energy auction, and the completion of private PPA projects.

Amid the reawakening of Spain’s PV market, there are a few political and administrative setbacks that may pose challenges for solar in the country, particularly for installations this year for projects that were awarded in the 2017 auction.

Political and regulatory struggles

In April, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party fell short of a majority and failed to form coalitions with other parties – another general election will be held on Nov. 10. This means that legislation for PV projects has not been approved, particularly regarding permits for grid connection.

The rush of renewable energy in Spain has created an incentive for speculators to buy rights to the country’s limited grid connection points. Permits are available for purchase without much review if the purchaser has the land or even the intention to build a plant.

Industry actors are calling for regulation to require purchasers that request permits to meet milestones and specify time frames to ensure project completion and deter speculation. However, the government stalemate has slowed the development of legislation that could tackle this issue.

Project deadlines and penalties

More than 70% of the 3.9 GW of solar projects that were awarded in the 2017 auction are completed or under development. However, it is unclear how far into the development process these projects are now. Nor is it clear if they have secured much-coveted interconnection points. In addition, for projects that secure grid connections, the local electricity network may not be developed enough to handle a large influx of PV. This could lead to curtailment, causing revenue losses.Of the 3.9 GW, more than 1 GW has yet to start construction. Projects are required to come online by Jan. 1, 2020. After this, developers will be required to pay “avales” (guarantees) for delayed projects or possibly renegotiate their terms. ACS Cobra, X-Elio, Northleaf and Enel Green Power were awarded the largest projects from the third auction, with ACS Cobra overseeing a pipeline of more than 1 GW.

Self-consumption opportunities

Royal Decree, 15/2018, came into force this April. The new law offers different modalities for self-consumption, including individual and collective installations with the possibility to inject surplus generation back into the grid. The collective self-consumption mechanism offers consumers the alternative of consuming a neighbor’s surplus generation and poses an opportunity for developers seeking to build portfolios of small systems.

Utilities also see value in the trend and have increased the promotion of their self-consumption offerings. Utilities are partnering with banks to offer attractive financial schemes to customers that install self-consumption PV. One of the main solutions is paying for the PV installation up front, and then charging the customer over future electricity bills. The amounts have been reported to go from €4,000 to €25,000 ($4,370 to $27,330).

PPA challenges

Corporate and merchant PPAs have been slow to gain traction in Spain due to several challenges. The two main ones are buyers committing to long-term contracts and financiers who are unwilling to share some of the risks involved with these schemes.

Large electricity consumers are less likely to sign long-term PPAs for a large portion of their power needs. The lack of standards slows down the PPA process as well, as each contract is individually formulated, with different risk allocation and conditions. The contract lengths for PV and wind PPAs that have been signed vary widely, demonstrating that there is no standard model for what kind of contract will work in the country.

This year, Spanish banks Banco Sabadell and Bankia have closed transactions for merchant projects, which signals that lenders are starting to become more flexible with their terms and conditions. Moreover, a recent PPA between Dutch brewer Heineken and Iberdrola indicates slow but marked demand for these types of agreements. Corporate and merchant PPAs in Spain will continue to face obstacles, but as these agreements continue to be normalized, improvements in the process will lead to stronger growth in these contract schemes.

Although there are political and transmission risks surrounding Spain’s renewable energy sector, participants are still confident about PV development. There is enough political pressure and investor demand to provide strong impetus for the government to carve out the proper incentives and regulation needed for the sector to grow.

Also read