Google’s reverse auctions net 1.2 GW of renewables in 60 minutes

Nov 2, 2019 09:50 AM ET

- Google pre-qualified bidders and used reverse auctions to obtain the lowest price for renewable energy. Reverse auctions for corporate purchases could potentially benefit solar developers, if their transparency and simplicity can influence more corporations to procure green power.

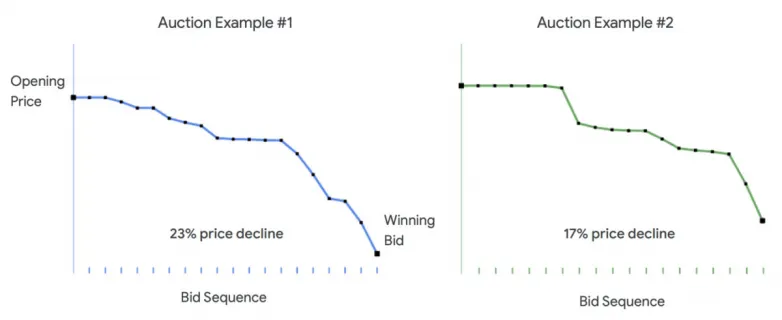

A Google case study of its reverse auction process shows the firm is pleased with the results, including finding the lowest bid in 60 minutes—as shown in the featured image—rather than through months of post-solicitation bid negotiations.

In a reverse auction for a solar power purchase agreement, many sellers (solar developers) compete for a contract with a single buyer (a corporation that will buy the renewable electricity). Some national governments and electric utilities have also used reverse auctions to procure solar and storage resources.

A reverse auction is similar to a standard solicitation process, except at the end. In one of Google’s solar solicitations, for example, once each pre-qualified bidder entered its first bid to deliver solar power in a specific settlement region, there was a 60-minute frenzy of price competition, as bidders could choose to offer a lower bid, if another bidder had undercut their last offer price. In two of Google’s reverse auctions, the bidding achieved price declines of 23% and 17%, respectively, below the lowest initial bid.

Google’s case study lays out the steps that Google took to execute a reverse auction, and the contracting documents that Google used. Google’s case study is enthusiastic about the process, but how well a reverse auction would work for smaller corporate renewables purchasers, and whether it also works well for solar developers, are open questions.

Advantage: Google

Google started off with a bang, issuing a global power purchase agreement request for proposals (global PPA RFP): “Globally we pre-qualified hundreds of projects, which led to hundreds of bids placed,” says the case study. Google, which claims the title as “the world’s largest corporate renewable energy purchaser,” could attract strong participation from solar and wind developers because it has a good credit rating, and planned to enter power purchase agreements for a healthy amount of capacity—1.2 GW.

Based on those bids, Google selected four regions that had enough bidders to support competitive bidding, and attractive project pricing—including the ERCOT and PJM grid regions in the U.S. In each grid region, Google selected one settlement region and one technology type per auction.

Google invited prospective bidders to meet qualification requirements relating to financial strength and a track record of completing projects. Qualified auction participants were shown Google’s standard-form PPA and term sheet. To participate in the auction, bidders were required to agree to the terms, and provide a bid deposit.

Then Google worked with a third-party technology vendor to run the auctions. Developers bid a total of more than 2 GW of projects into the four auctions, which proceeded quickly, over 45-60 minutes each, as Google staff “watched in real time as bids flowed in.”

The only remaining step was to sign a contract with each winning bidder. Google signed ten power purchase agreements, representing more than 1.2 GW of renewable capacity. There was no lengthy post-bid negotiation process, as is typical in solicitations without an auction mechanism.

Google noted price as a key benefit. “Our reverse auction allowed us to meet our renewable energy procurement goals at costs that were … meaningfully lower than we would have obtained via a traditional request for proposals (RFP).” Yet Google did not indicate how much of the cost savings came from first identifying the four global regions most promising for conducting an auction.

Speed was a key benefit as well, as Google was able to complete four renewables procurements in less than a year, whereas previously it took 18-24 months for a single procurement.

Advantage: Solar developers?

It’s possible that reverse auctions could serve the interest of solar project developers as well, if:

- Each buyer—or consortium of buyers—commits to enter power purchase agreements for a substantial amount of renewable capacity in each auction, as Google did

- The process becomes standardized across buyers, with relatively standard documentation requested of solar developers

- A transparent reverse auction process using standardized forms attracts more corporate buyers to the market

- The absence of post-bid negotiations provides significant savings to developers.

Google’s hopes

Google expressed concern that “it still remains too complex and too costly for most organizations to buy renewable energy (RE),” adding:

We hope to see RE auctions become more useful to a broader array of energy buyers. Platform services, consulting intermediaries, or brokers could enable buyers (or consortiums of buyers) that lack our resources and expertise to participate in RE auctions. Additionally, purchasing contracts could be further standardized.”

Google said that beyond auctions, it is also exploring “new marketplaces for RE,” as well as “demand aggregation projects that enable smaller energy buyers to act as large buyers in the market.”

Google’s goal was to offset its electricity consumption with renewably generated electricity, produced anywhere in the world. Since greenhouse gases travel globally in the atmosphere, that makes sense. And accelerating solar deployment anywhere in the world helps advance the solar industry globally. So Google’s global approach is one that other corporate renewables buyers could also consider.

Yet Google’s case study made no mention of the price risk faced by firms that enter power purchase agreements, and plan to sell power into the wholesale market: as more renewables projects are deployed, wholesale electricity prices during sunny (or windy) periods will fall. Adding storage to a project, or purchasing a financial hedge, are ways to mitigate price risk. Bearing price risk without any such “insurance” may be affordable for Google, but could be too risky for other corporate purchasers.

While some school districts have made publicly available their RFPs for solar-on-schools PPAs—helping other school districts pursuing the same goal—Google has not chosen to make its reverse auction contracting documents “open source.”

Also read